#SH302: Seeing Results in Action–3 Practices for Any Organization

Most of us go to our graves with our music still inside us, unplayed. ~ Oliver Wendell Holmes

Businesses and educational institutions alike are built on the idea that what matters is performance and results. Granted, they may differ in the sense that one may focus on profits while the other turns to academic gains as the benchmark, but the process of driving toward a measure of achievement is the same. A clear well-defined goal, a thoughtful strategy, high engagement, and proper execution are shared elements in any organization that evaluates its success. Whether it is within the boardroom or the classroom, the critical factor in supporting the work is through people, not policies, initiatives, or programs. For goals to be accomplished, the individuals doing the work must do it well, which takes effort, energy, supportive cultures, and general well-being. The riddle lies in creating an environment that supports the people without exhausting them. Too often, especially in high passion professions, people burnout, results suffer, and working toward a product becomes the enemy of any enjoyment we get in the process (Moss, 2019).

To understand this further, we like to use the incredible feat that was accomplished on May, 6th 1954 on the Iffley Road Track when Roger Bannister broke the 4-minute mile. It was an amazing achievement that Bannister accomplished, being the first in history to cross the mark. In fact, no one believed it could happen. Doctors even held a long-standing theory that it could kill a person to go that fast. Bannister changed that. But, then, just a few weeks later, John Landy, another middle-distance competitor, broke the barrier as well. If you want to talk about seeing results in action, there’s no better place to watch things unfold than on a track. Cars, people, go-karts, it matters not–the results are real, and they happen right before your eyes.

Because this record was so great, the story is often told about “achieving the impossible.” And Bannister’s training regiment was minimal, making the story that much more unreal. He was only afforded one hour a day to train, which was due to his medical studies. But, two parts to the story are typically left untold, and we find them to be the most important when we talk about leadership lessons in putting results into actions. First, Bannister wasn’t just your ordinary middle-distance athlete. He trained at Paddington Recreation Ground near St. Mary’s Hospital where he was also training to be a medical doctor. His studies just happened to focus on autonomic failure, the nervous system, cardiovascular physiology, and multiple system atrophy. In other words, he knew a little bit about the human body when he busted the contemporary theory about the 4-minute impossible measure. Second, because his training was limited, he devised a process that would only today be considered a very modern training program. With influences from the greatest runners and coaches he could find, he used an interval training process that included a number of anaerobic performance enhancers. In summary, to put results into actions, Bannister focused on a specific process, the conditions he needed to be his best, and engagement in both his studies and track time. Here’s what we can learn from Roger Bannister:

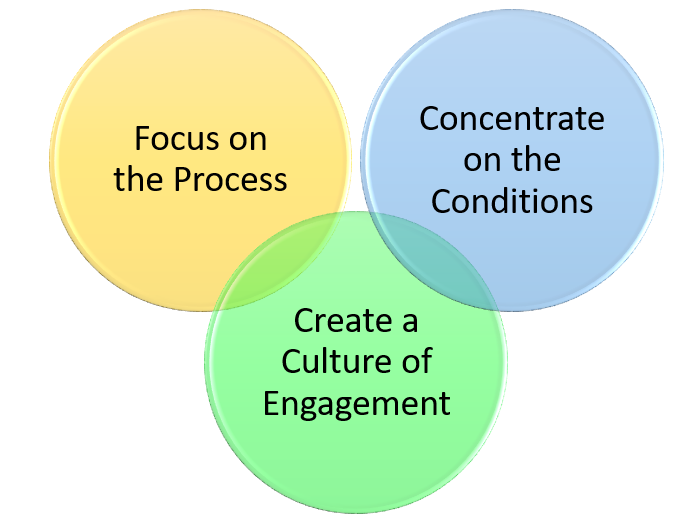

Focus on the Process, Not the Product — #performance

“Results are outcomes brought about by actions…great leaders focus their efforts and energy: on the process, not the outcome” (Edinger, 2018). This shift, from a results-driven mindset to an actions-driven mindset, may seem counter-intuitive at first. We live by the phrase, “what gets measured, gets done.” But we can’t always measure the work while we’re doing it. In fact, too many of our measures are long-term goals and not centered on the work at hand. Great athletes, like Roger Bannister, know that the outcome, winning or beating the record, isn’t accomplished as a mere act, but rather the actual work that was put into the process of striving for such an audacious goal. In other words, as we focus on the process of our work, not just the product, we begin to see that our daily, even minute-by-minute, performance is what matters most. Results come from our daily practice, specific feedback, and consistent effort toward the goal. Great leaders focus on the way the team is performing, not just it’s overall achievements. This brings us to the conditions in which great teams perform well.

Challenge Question #1: How can you create a culture where each individual monitors his or her own performance to determine progress toward the predetermined goal?

Concentrate on the Conditions, Not the Bottom-line — #resources

The conditions we set for the people to achieve our desired results must reflect our regular actions as leaders. What we do with our behaviors must match the vision we communicate, the core values we tout, and the goals we want to achieve. Too often there is a gap between what we want as the bottom-line and the way we support the people in getting there. It’s the leader’s role to consistently be working toward “shaping a culture that provides the conditions for individuals to perform” at their best (Center for Creative Leadership, n/d). Conditions include resources, like time and access to tools, but also working benefits, like professional learning experiences and upward mobility. When workers have what they need to perform at their best, the results happen right before our eyes. The key is that our demand for excellence and our need for bottom-line results must not be in contrast with the positive working conditions that allow both to happen. As leaders focus too intently on the bottom-line, we can quickly lose focus on the people or, worse yet, limit the resources they need to do their jobs well. Bannister had both the medical knowledge to debunk the myth and the conditions he needed for deliberate practice. Your team needs the same.

Challenge Question #2: How effectively are you communicating the overall goal while maintaining a culture of care and compassion?

Create a Culture of Engagement, Not a Culture of Exhaustion — #fun

Too often, the leaders who are results-driven are not the same who we consider when we think about great teams and fun places to work. But that’s not true about ideal leadership. In fact, one study found that “not only is it possible to do both things well…the best leaders are the very ones who manage to do both” (Zenger & Folkman, 2017). When we think of productive cultures, we too often gravitate toward task-masters, but that type of thinking is antiquated at best. Great leaders of the future will have an absolute focus on a people-centered environment, and they will reap the benefits of discretionary effort, an engaged workforce, and a happy place to spend their days. The key strategy is to know your workforce and their particular needs as people. Not all cultures will benefit from a foosball table and longer lunch breaks, but your people will certainly engage more with their work when you consider ways to prevent exhaustion, stress, and burnout. Bannister only had one hour a day to train, but, with full engagement in the program, he made the best of it, which ended up being more productive than his competitors who were putting in more time only to exhaust themselves.

Challenge Question #3: What’s one new perk that you can provide your people for a stronger sense of work-life fit and personal well-being so that they can be even more productive and engaged at work?

Now back to John Landy, the guy who broke the barrier only weeks after Roger Bannister. The significance of Landy breaking Bannister’s record provides leaders with incredible insight into the power of self-belief. Landy doubted his ability to break the 4-minute barrier until Bannister showed that it was possible. Landy’s accomplishment reveals that Bannister was not a lone nut. As the first follower, Landy demonstrates to the world, again, that the impossible is actually possible and that it can be achieved by more than only one person. Positive contributions to any given society are the result of a process, the right conditions, and a group of people whose belief in something bigger than themselves is so strong that it creates a following. Landy symbolizes the future of putting new action into reality on the race track. And, following in his lead, 100s and 1000s of runners break a 4-minute barrier each year, without any consideration for it being impossible. Bannister, then Landy, then the rest of humanity, at least the elite running community that is–those who care to develop a training program, who create the conditions for success on the track, and who engage on a regular basis with the work. That’s leadership.

But one more thing about Landy. In 1956, at the Australian National Championship, he stopped during a race to check on another runner who had fallen after being clipped at the heel. Not only did the runner get back to his feet to finish the competition, Landy made up for the deficit to miraculously win the race. Kindness is always an action that produces results.

You can see your results in action, too, when you develop a process, provide yourself and others with the right conditions, and create teams of people who are committed and engaged in the work. More than ever, a focus on happiness at work is emerging as the key structure for productivity (Moss, 2016; McKee, 2018). Reach out to us with the ways that you’re putting results into action, including an increase in happy workers in your organization. We can’t wait to hear from you.

Let us know what you think of this #SH302 post with a like, a follow, or a comment. Find us on Twitter, YouTube, iTunes, Facebook, & SoundCould. And if you want one simple model for leading better and growing faster per month, follow this blog by entering your email at the top right of the screen.

TheSchoolHouse302 is about getting to simple by maximizing effective research-based strategies that empower individuals to lead better and grow faster.

References:

Center for creative leadership (n/d). Bridging the strategy/performance gap. Retrieved from https://www.ccl.org/articles/white-papers/bridging-strategy-performance-gap/

Edinger, S. (2018, October 10) The Myth of Leaders Driving for Results. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/scottedinger/2018/10/10/myth-of-leaders-driving-for-results/#75428ebad94f

McKee, A. (2019). How to be happy at work: The power of purpose, hope, and friendship. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Moss, J. (2016). Unlocking happiness at work: How a data-driven happiness strategy fuels purpose, passion and performance. London: Kogan Page Limited.

Moss, J. (2019). When passion leads to burnout. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2019/07/when-passion-leads-to-burnout

Zenger, J. & Folkman, J. (2017, June 19). How managers drive employee results and engagement at the same time. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2017/06/how-managers-drive-results-and-employee-engagement-at-the-same-time

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.