A culture of excellence requires time, commitment, and ongoing care. To cultivate excellence, it must be rooted in professional dialogue to launch and sustain your organization’s growth and development, which requires employees to be engaged. Unfortunately, employee engagement remains an issue in the workplace with poor communication being one of the main culprits. One Gallup study of “7,272 U.S. adults revealed that one in two had left their job to get away from their manager to improve their overall life at some point in their career” (Harter & Adkins, 2015). Too often “people sense that they [are] missing needed information, [and] they blame lack of communication for the problem” (Markman, 2017). The fact is that proper communication and professional dialogue rest at the heart of every great organization’s infrastructure.

How an organization communicates to deal with the realities facing them will be the basis for either growth, stagnation, or eventual failure. The problem is not normally information sharing or access but rather how well we communicate with one another that makes the difference. To create a culture where communication is woven into the fabric of the organization, we’ve developed a five-part model to guide leaders and to ensure that poor communication doesn’t sink their best efforts.

Everyone Loves Samantha, But…

Samantha possesses the interpersonal skills and positive attitude that everyone loves in a coworker, yet, at times, she can pose issues with behaviors that hinder the team and get in the way of productivity and the team’s output. Her technical competency and depth of knowledge are good, but she has tendency to talk by the “water cooler” a little too long and can easily derail a meeting with an off putting joke or misplaced story. The difficult thing about Samantha is that her strengths, at times, become her weaknesses; her team perceives her more as a tension eliminator versus a problem solver.

The biggest issue for Dan, her manager, is that he wants to talk to her to get her to balance her levity and off-task tendencies with her potential for substantial contributions. She is certainly loved by her peers, and so Dan fears that a conversation with her about this will shut her down and alienate other team members who may be used in the examples that Dan has to demonstrate the problems. At the end of the day, he struggles with whether or not the conversation is even worth it. Samantha brings humor and laughter to the meetings, she gets her work done, but Dan and the team need more than that from Samantha.

What Should Dan do?

We would love the situation to be straightforward, suggesting that a simple conversation will do the trick, but we know that growth and development take time and resourcefulness on the part of any leader. Samantha is loved by her co-workers, and she possesses a vibrant energy. In the end, we need to ensure that Samantha is clear about the needed changes, that she recognizes her need to grow, and that the terms and conditions are agreeable. Not only is Samantha’s attitude toward growing critical to her success, it’s pivotal for the organization’s culture and the support that ensues when people are ready to make needed changes.

Dan needs to be straightforward with Samantha and any waiting to communicate will only exacerbate the problem. He needs to address her behaviors as soon as possible. He also needs to be clear about the fact that her strength is her ability to provide a positive energy and that her potential as a contributor is clear but that her off task comments can stress the team in times when she thinks she’s lightening the load.

Dan has to be candid, confronting reality with expectations and timelines. He can’t sugarcoat the situation or it will be misunderstood. Managers have a distinct need to demonstrate that they are in their employees’ “corner,” establishing and systematizing professional dialogue in the workplace, but with candor at the same time. The notion is that leaders care so much that they can tell you what you don’t want to hear in a way that balances the need to communicate a problem with the nurture and support to help make the changes together.

Communication is Often Counter-intuitive

As leaders, it’s critical that we focus on growth. We have to do what it takes for our team and for ourselves to develop over time. This means that organizations have to put core values at the center of every decision. If a core value is professional growth and personal development, then feedback and dialogue are critical drivers for performance. One step in keeping the norms at the forefront is in setting clear norms for communication and understanding the pitfalls in what we think we said and what we think we heard from others.

These norms have to be established within the culture and modeled by the leader. There are three critical norms that the leader must set, holding everyone accountable to the way that communication takes place:

- Accept the norm that feedback is candid and welcomed by all.

- Accept the norm that feedback is frequent and meant to drive positive changes in performance.

- Accept the norm that we must review and reflect on what we’re writing and saying to one another on a regular basis so that the quality of our feedback improves.

This means that all dialogue considers the balance between communicating clearly because of our position in the team’s corner and our care for the people. In the center of clear communication and compassion for the people is always the candor it takes to help them get better.

We know that some conversations can be difficult. Particularly, with individuals who contribute positively but who also have flaws that need to be addressed, communicating can be excruciating. This is precisely why leaders need to create a culture of candor and compassion with feedback at the core. But before we fully introduce a model for crystal clear communication and professional dialogue, we need to address a common assumption about the lack of information sharing in any organization. As Judith Glaser, an organizational anthropologist and author of Conversation Intelligence, reminded us in our #onethingseries podcast interview (coming up this month): “our words create worlds” and “we often don’t say what we really mean.”

The Assumption: Information is the Solution

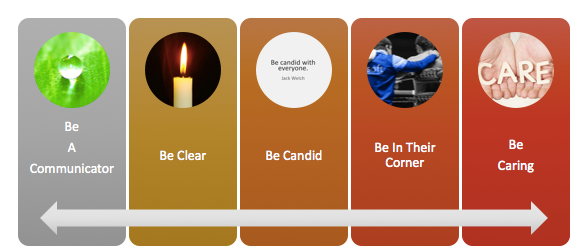

Too often, when communication is pinned as the culprit, we jump to conclusions that there’s a lack of information sharing in our organization. Folks even say things like “had I known…” or “no one shared that with me…” And, as leaders, we tend to believe that “greater access to information is the solution” (Markman, 2017) so we develop stronger methods for communicating, like newsletters and bulletins. But more or different communication channels are not likely the answer because procedures for communicating aren’t usually the problem. It’s more likely to be the way we communicate, how we interact with people, than if we are communicating. You can eliminate the fear of providing feedback by using these 5Cs of professional dialogue.

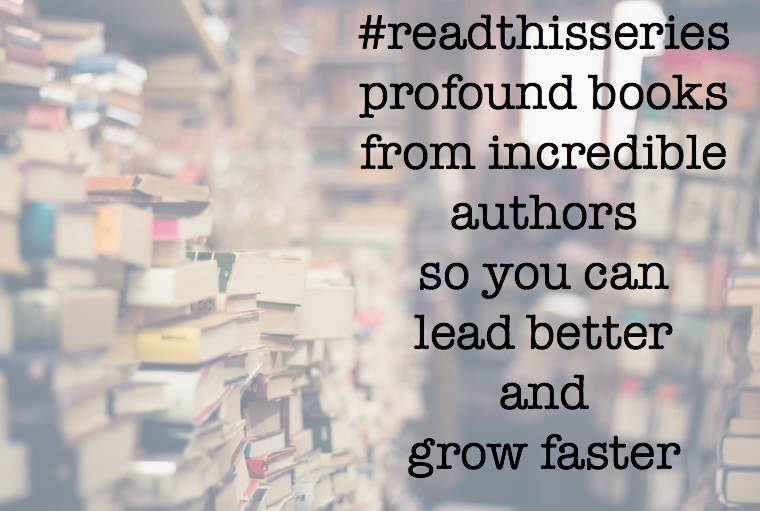

The 5Cs of Professional Dialogue

Be a Communicator: Are your organization’s goals communicated well enough to use in a conversation regarding performance?

The first C is to be a communicator in the first place. Too many leaders fail to communicate, and that’s simply not acceptable. The bottom line is that strong communication is grounded in the mission, vision, and goals of the organization. Leaders must over-communicate the purpose and meaning behind the work. If you haven’t communicated the goals of your organization often enough to hold others accountable to them then they might as well not exist. Dan should be able to use the department’s goals to demonstrate a performance gap for Samantha. If he can’t, the goals for her performance aren’t clear enough.

Be Clear: Is your feedback clear enough for others to take action?

Achieving clarity around the goals and values is the backdrop for quality feedback concerning an individual’s personal actions or a team’s accomplishments. This type of clarity with communication allows for all professional dialogue about performance to be more objective. In the case of Samantha, it means pointing out her strengths and weaknesses based on pre-defined organizational expectations, which are not the arbitrary personal standards of the supervisor. Remember that this means two things: 1. the mission, vision, and goals have been communicated and 2. that the feedback is clearly tied to them. Too often, we fall into the trap of assuming that the goals are clear when they’re not or we give feedback that isn’t clearly linked to the goals. In either case, we’re not communicating clearly and subsequent improvements won’t be made.

Be Candid: Is your feedback specific, candid, two-way, and ongoing?

The third C is candor. Being candid while maintaining a two-way, open dialogue, requires serious skill. It also requires a high degree of competence with the aspects of Samantha’s performance that you’re addressing. Too often, candor has a negative connotation because it is associated with a difficult message or with a frankness that’s too abrupt. We maintain that candor is simply direct and specific feedback, which everyone needs, and should be presented in a manner that is designed to be open and honest. In an interview with one of the greatest boxing trainers ever, Angelo Dundee makes it clear why his relationship with Muhammed Ali was so successful: “I was always very honest with him. And him with me.” Dundee recalls how he could simply mention how Ali’s jab looked and how Ali would work on it until it was right. Embracing candor as the vehicle for improved performance builds a culture that accepts and expects feedback for improved performance. Candor also increases the speed of the desired improvements. It accounts for specificity with the needed changes versus the flowery and ambiguous feedback that leaders sometimes provide in an effort to “be nice.”

Be in their Corner: Does your feedback communicate that you’re in the person’s corner no matter what you’re saying?

The fourth C of our professional dialogue model is communicating that you’re in the corner of the person with whom you’re feedback is directed. People are not always going to like what you say, especially when it’s critical about an aspect of their performance at work, but they’ll be far more likely to accept the message if they know that you’re with them in their efforts to make improvements. Consider Samantha, the only way she’s going to get better is if someone points out her performance issues to her. She’ll likely respond in one of two ways: defensively, which is a result of her feeling alone in her efforts to improve or acceptance, which is the result of her feeling like the message is coming from someone who stands in her corner with support and resources. The difference looks like this:

- Samantha, you need to make some changes or we’re going to have to talk about an improvement plan for you.

- Samantha, you need to make some changes, and I’m here to support you with some strong advice and a few resources that can help. Let’s work together on this so that you can improve your performance and contribute on greater level, which I’m confident you can do.

The first example is almost an ultimatum, and sometimes people do need real documented improvement plans, but it leaves Samantha hanging out there alone versus the second example, which commands the same message but shows that the leader is there to help and not just to evaluate.

Be Caring: Do your words and actions demonstrate care for the people in your organization?

The fifth and final C in the professional dialogue model is demonstrating care. If the leader truly cares about the people in the organization and demonstrates care through actions and words, the people will be motivated and inspired to put forth effort and improve the quality of their performance through feedback. We can’t just want Samantha to improve for the sake of the organization. We have to care about Samantha–her personal needs, her sense of efficacy, and her feelings about the job she does–before we can spend any time enhancing her performance through critical feedback. Leaders who care do so with specific actions and words. Sinek metaphorically describes this by saying that “leaders eat last.” By eating last, providing food, making work fun, and uplifting others, leaders can demonstrate that they care about people.

If you communicate with people, you do so clearly, you employ candor, you demonstrate that you’re in their corner, and you show care, you’re leading in a way that should prevent any fear from giving feedback to the people on your team or in your organization. This type of professional dialogue is exactly what leaders need to propel their teams into the future. That’s our model for professional feedback, and we hope it helps you to lead better and grow faster.

Let us know what you think of this #SH302 post with a like, follow, or comment. Find us on Twitter, YouTube, iTunes, Facebook, & SoundCould. And if you want one simple model for leading better and growing faster per month, follow this blog by entering your email at the top right of the screen.

TheSchoolHouse302 is about getting to simple by maximizing effective research-based strategies that empower individuals to lead better and grow faster.

Joe & T.J.

References

Gallup, Inc. (2015, April 08). Employees Want a Lot More From Their Managers. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/236570/employees-lot-managers.aspx

Markman, A. (2017). Poor communication is often a symptom of a different problem. Harvard Business Review.

Sinek, S. (2014). Leaders eat last: Why some teams pull together and others don’t. Penguin Group: New York.

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.