Retaining Teachers: 3 Important Strategies for School Leaders

Teacher Retention: A School Leader’s Top Priority

Teachers have three loves: love of learning, love of learners, and the love of bringing the first two loves together. ~ Scott Hayden

Retaining teachers is at the top of the priorities for every school leader. This has always been true; effective school leaders have always worked to retain their top talent. But, these days, school leaders are counting their blessings if they’re fully staffed. The teacher shortage is real, and although it has impacted some regions of the country more than others, having a quality teacher in front of every student is a must. “More teachers are choosing to leave the profession, with the teacher supply shortage expected to reach 200,000+ by 2025.”

One problem with teacher retention is that school leaders don’t always have the tricks, tips, and tools associated with technical human resource training. The fact is that school leaders haven’t traditionally thought about their schools within the marketplace of hiring and retention. We’ve argued that school leaders ought to think about things like branding, marketing, storytelling, and recruiting–all important aspects of being a great place to work and filling vacancies quickly when they arise. The truth is that retention starts long before you have positions to fill. That said, we have to work hard to keep the people we have by making our schools the best places possible to work and learn.

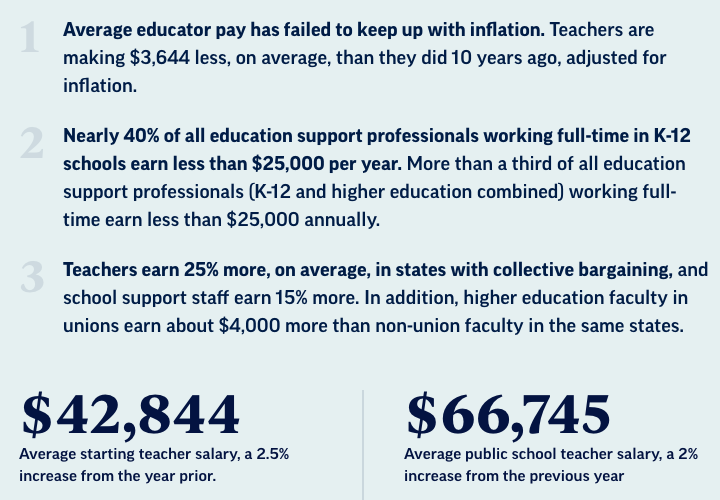

Remember, though, there are things that are out of your control as a school leader. You probably can’t alter the compensation and benefit package that your school or district offers, sweetening the pot to keep people from leaving (see picture below regarding teacher pay). You also probably can’t change work hours, increase flexibility, or give people more days off. The rigidity of the profession is contributing to the diminishing number of people entering it. But, this shouldn’t stop us from pushing back on these boundaries or putting forth the effort to create an awesome environment for teachers.

Source: NEA, Educator Pay Data

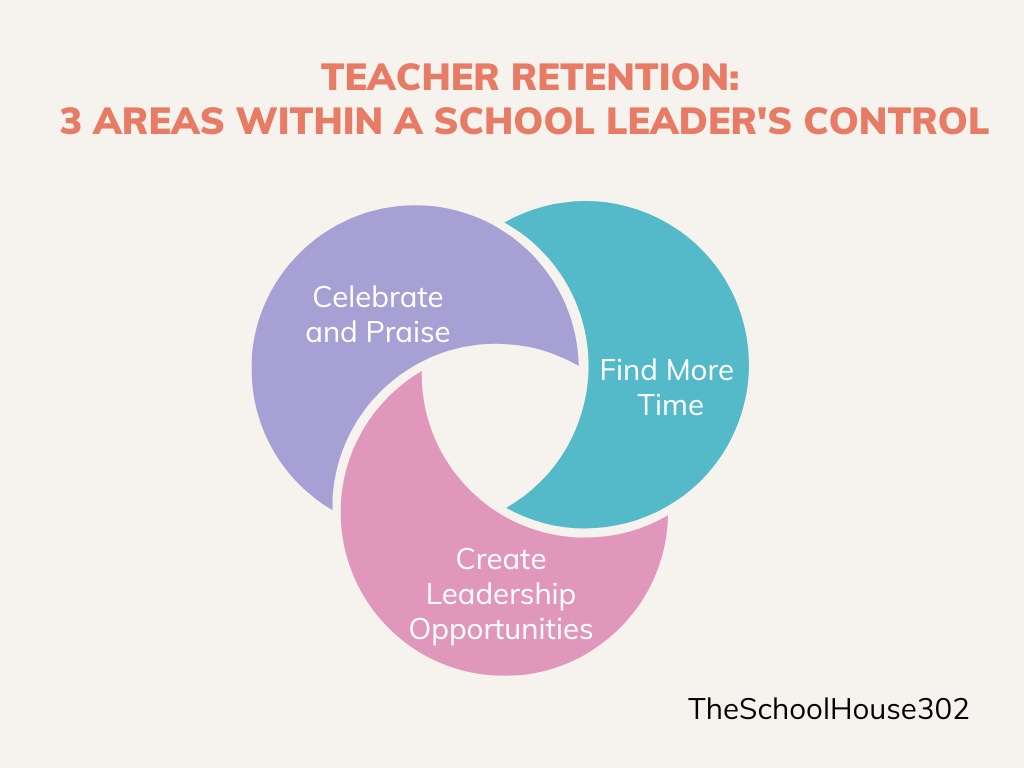

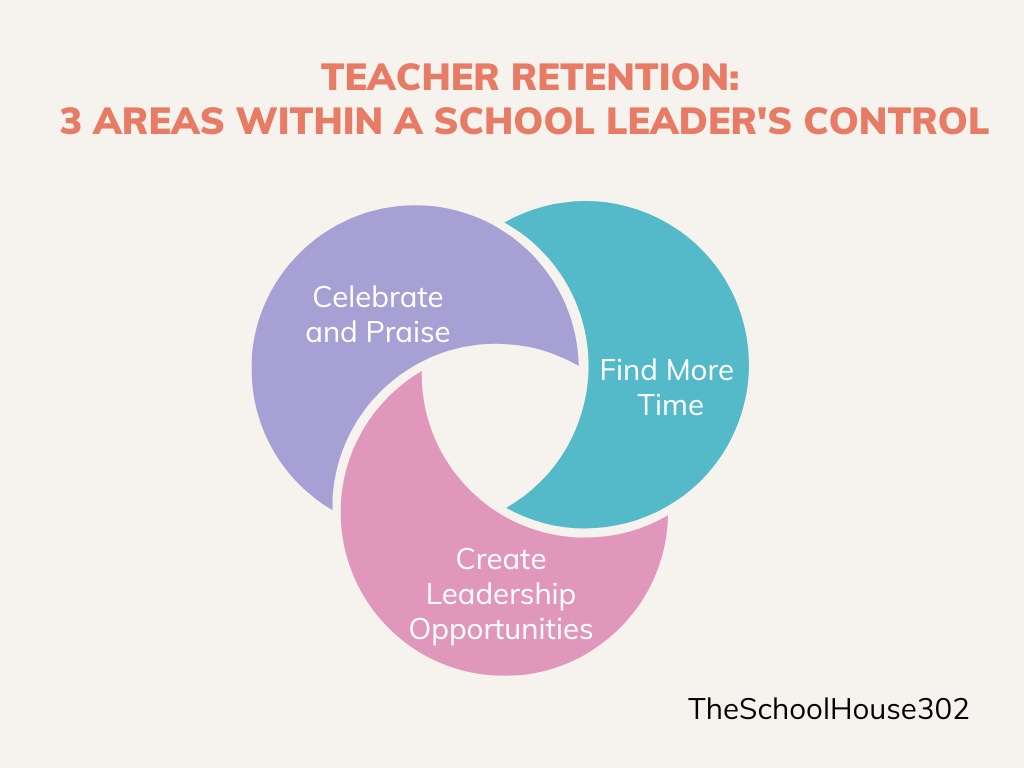

Let’s talk about what we do have within our sphere of influence as school leaders. We want to bring three critical areas of educator retention to the forefront of your mind. The first may seem simple and obvious, but the data tell us that managers around the world, including school leaders, get it wrong and don’t do it enough. The second may seem out of reach given the constraints we listed above, but that’s not the whole story. And, the third is a missed opportunity in schools to build collective efficacy while putting your teachers’ voices on center stage. Let’s dig deeper.

Three Critical Areas of Educator Retention

#1. Celebration and Praise Your Teachers

Praise in the workplace is arguably the most misunderstood and underused form of feedback. We train school leaders how to use specific praise in districts all over the country, and it often takes months and years before the power of praise is realized through effective language selection. One reason for this is that our brains are wired to find the negative so your praise may be falling short for the mere fact that your teachers are looking for what you’re pointing out that they did wrong versus what you may be trying to communicate that they did right.

We built a praise model in Retention for a Change that’s steeped in research from neuroscience and behavioral psychology. We wrote about it again in Invest in Your Best (to be released in December of 2023). Here’s a sample that you can use for practice in your school. The point is that your praise needs to use language that is very clear to the receiver that you’re impressed, happy, and excited with their work, that you’re specific about what it is you’re praising, and that you provide a reason for the importance of the desired outcome of their work. We praise people for two results: increase their pride and fulfillment with their achievements and reinforce what they’re doing that we want them to repeat or do more often.

Unfortunately, many school leaders and organizational managers use praise sparingly, sometimes on purpose. We get this question all the time: what if I use praise too much and people become less focused on improvement because they think they’re good enough? If you use praise well, that won’t happen. The opposite is true. Praise is motivational, inspirational, and energizing. The good news is that with leaders out there who think like this, your school can be a place that attracts and retains talents because you’ll be using praise well and more often than other school leaders.

#2. Find More Time for Teachers

Many teachers would actually like more time for their job-related tasks than they would like more money to do them. We’ve seen survey results that demonstrate that teachers rank the need for more time over the need for increased pay. Wow! That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t also pay them more; we’re advocates for better compensation for educators, but, like we said, that’s more likely to be out of your control as a school leader than the time requirements that you put in place for your staff.

This is another important strategy for retaining your teachers, and one that we dedicated a chapter to in Invest in Your Best. Especially with your most valuable staff members, the last thing you want them doing is spending their time on tasks that don’t result in the impact that they have the potential to achieve with students. The goal is to analyze and inventory all of what we ask our teachers to do day-to-day. Each day matters. What are the regular daily routines and duties of our teachers? What do we ask of them on professional learning days? And, what types of reports and paperwork are they submitting? We have to think about eliminating anything that isn’t directly associated with teaching and learning.

Here’s a quick list of 6 questions to think about with your school leadership team:

- Do our teachers have duties that put pressure on their planning time? Is it essential to have them do these things or can we find another way?

- How much planning time do we have within the work day and can we increase that…even by five minutes?

- Are there reports, lesson plans, PLC minutes, observation forms, etc. that we can eliminate or streamline?

- What do our professional learning days entail? Can we give teachers a period of reflection time on PL days and decrease the “learning time” from 6 to 4 hours (as an example)?

- Are there days in the year–PL days, beginning and end of year days, etc–that we can make more flexible?

- Do we have any days of the year or partial days where teachers can work from home?

We’re not devaluing professional learning or even the need for teachers to cover lunches and recess, but the exercise of answering these questions on a regular basis should give you some ideas about how to create time and space for your teachers. With these questions in mind, as you approach a professional learning day, for example, you may realize that there are opportunities to create flexibility.

One last aspect of time. Everyone has the same 1440 minutes in a day and not all people manage those minutes the same way. How we view time is often driven by our perception of it and our capacity to use it. This means that as a leader you can capitalize on others’ perception of time by helping them manage themselves better so that they can accomplish more. In short, don’t assume that people know how to take a series of tasks within an allotment of time and complete them efficiently. Our job as leaders is to help everyone else maximize their potential and help them learn to navigate their day effectively amid all the demands.

#3. Create Leadership Opportunities for Teachers

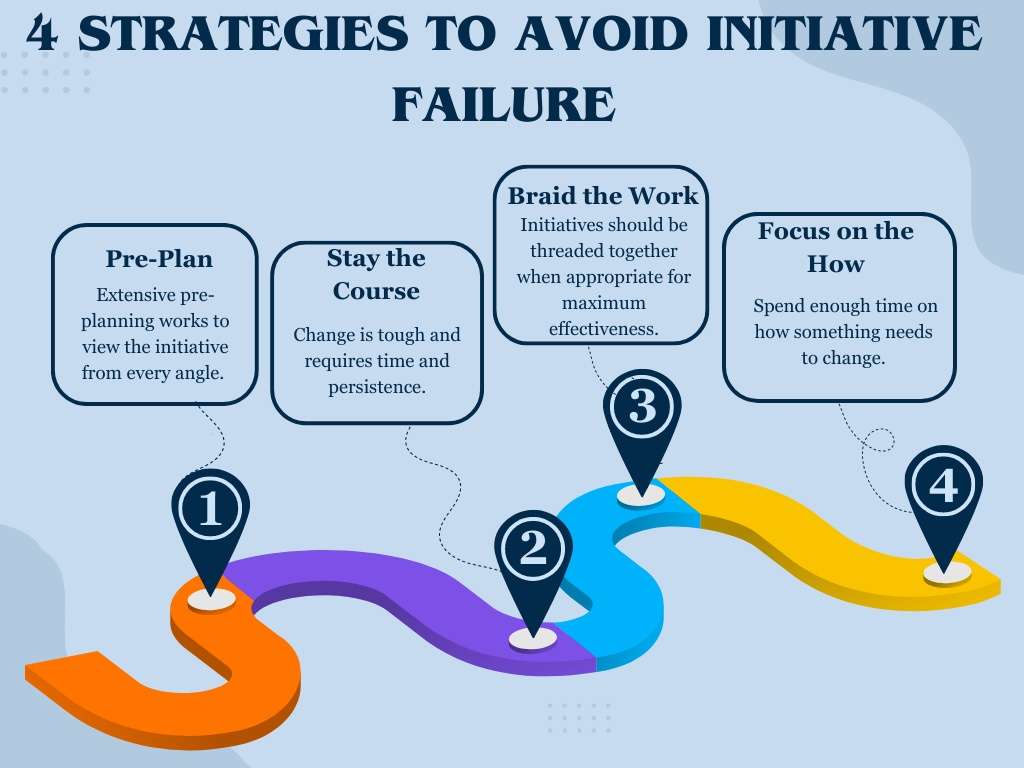

When we consult with schools and districts, and we find out that they don’t have a school leadership team–composed of teacher leaders–it’s the first thing that we help them to develop. After that, we help them to build the capacity of their teacher leaders to take control of new initiatives so that they unfold successfully. Here are the two basic concepts:

Concept #1: School leaders can’t do everything themselves. They need a supportive and reliable team.

Concept #2: Great teachers don’t automatically make great leaders. Their prowess in the classroom doesn’t change the fact that they need leadership training. Our best teachers have the potential to lead, but only if we support their growth and development.

We contend that the all-hands-on-deck approach is the only way that great schools thrive, and that a positive school leadership team is the best avenue to collective teacher efficacy. In a school environment where both are true–everyone working toward the same goal with teachers at the helm–you’re retention efforts don’t land squarely on your shoulders but live within the culture of the school itself.

The Final Word on Teacher Retention

We were talking to a school principal recently, and he was worried about a position he had vacant and the lack of applicants in the pool. We asked him what he was doing about it. Perplexed, he told us that he was checking the posting several times a day, but nothing beyond that effort. Unfortunately, postings alone fall short. They are a great traditional method of hiring, but there are countless other steps to take.

We gave him several strategies for becoming far more aggressive in his outreach, including a search on LinkedIn that we modeled, which revealed several teachers in the area who were #OpenToWork but who certainly didn’t know about his posting.

The point of the story is that attracting, recruiting, and retaining talented teachers has to be strategic. Gone are the days of passive culture building or relying on the HR department to fill our positions. School leaders need to learn to play an active role in maintaining a culture that teachers desire. Using praise, finding time, and developing teacher leaders are at the top of our list of ways that we can work to retain teachers, and we hope that you find value in making an effort in these areas in your school or district.

As always, we want to hear from you. Please hit us with a like, a follow, a comment, or a share. It helps us and it helps other readers, like you, to find our work so that more school leaders can lead better and grow faster.

We can’t wait to hear from you.

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.