We hear of incredible stories of accomplishment amid severe hardship and constant rejection. Whether we consider Abraham Lincoln’s early failures in politics and business, and revere his perseverance at becoming one of our greatest presidents. Or using a more contemporary example, we look to Stephen King, a great American author, who in pursuit of his dream found rejection with his first novel, Carrie, being dismissed by publishers over 30 times (Demers, 2015). We know that many successful people endure major setbacks, both personally and professionally, as life itself presents a series of challenges that crush some of our greatest desires and goals. Whether in politics, business, writing, sports, or any aspect of life, failure is natural, trials occur, and misfortune becomes almost commonplace. How we view and perceive our failure determines whether the experience is beneficial and continues to move us toward our goals…or not. And as failure has somehow emerged as a prerequisite for leaders, the notion that great leaders have to fail first to be able to succeed, we want to address this concept of failing in order to achieve greatness in two ways:

- It’s not a farce that leaders often have countless failed attempts before making it big, earning them fame or fortune or some other glory. Not all leaders have to fail to be successful, but it is true that persistence is a key leadership attribute, and those who fail and “try, try again” are the ones who are most likely to succeed. We think this is mostly due to the grit that is defined as pushing forward after a failure (Duckworth, 2016) than it is due to the nature of needing to fail.

- Failure comes in many forms. The simple definition of failure is usually something along the lines of “a lack of success.” But, this lack of success isn’t always due to a failed attempt, but rather an omission of a critical action necessary for success. In other words, failing to lead is mostly something that happens when we fail to take action because we fear that our actions won’t lead to our desired outcomes, and we focus on the product of our efforts and the lack of clear results that we see along the way.

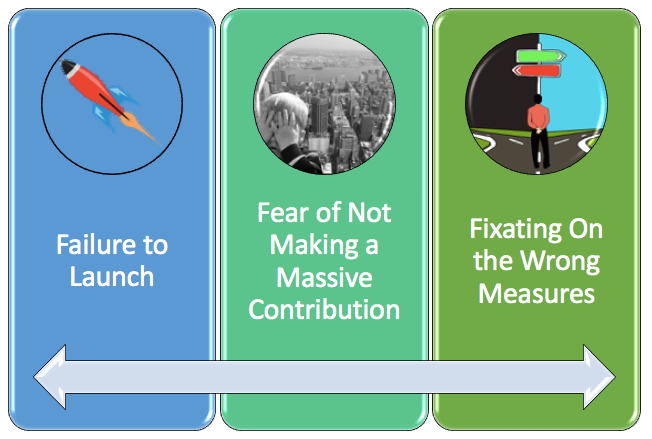

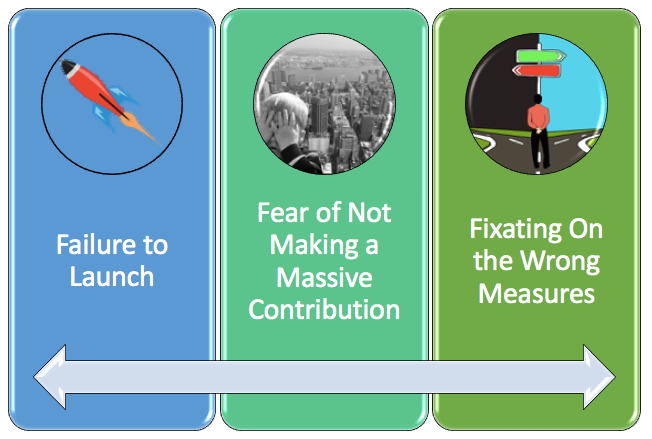

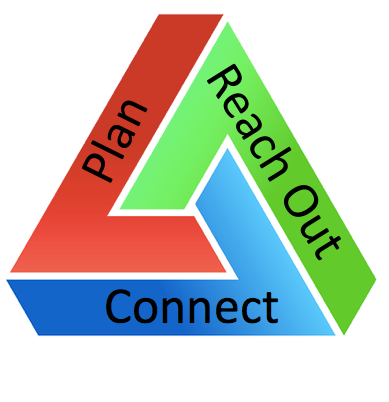

Great leaders know that to win, risk is almost always necessary. And although there seems to be a glorification of risk-takers as leaders in our society, most great leaders know that when they’re venturing into uncharted waters, the best thing to do is to mitigate risk. So two concepts emerge around winning from failure. The first is that failure is necessary, but we contend that failure is typically a result of inaction, fear that our goals won’t be achieved, and a lack of clarity around what we truly desire. The second is that leaders are risk taking daredevils, and with that we note that leaders certainly take risks but never blindly. For these two reasons, we have a model, not for how to fail and succeed, but rather how to not fail to take calculated risks in life and business. Avoid earning yourself these three Fs on your report card of success and you’ll fail forward with the greatest leaders of all time.

F#1: Failure to Launch–you can’t fail, if you don’t try.

“I can accept failure, everyone fails at something. But I can’t accept not trying.” ~ Michael Jordan

The biggest failure of them all is not even giving yourself the opportunity to fail in the first place. The leaders who failed before they succeed all had one thing in common–the didn’t fail to try. The problem is that people tend to make 100 excuses as to why it’s not possible to move forward versus 1 excuse to take action immediately.

The reality is that we want things to be just right before taking the first step. Although planning and preparing are critical aspects of any successful endeavor, the conditions for launching a project are never perfect. Too often, leaders are in pursuit of perfection when perfection can be the enemy of making any progress at all. This is where we bring back the concept of risk-taking. Failure to launch a project is either a symptom of not enough planning or too much. If you’re in the preparation stage, taking time to mitigate risk, it’s time to make a move. Ron Ashkenas, author of Simply Effective, says that executives can get caught up in research before taking action, but we need to shift that thinking to the notion that “action can occur parallel to research” (2011). Your project likely has many steps, but launching it only takes the first one.

Practical Example: Consider Jan. Jan was unhappy in her current job, deep down she always wanted to be a teacher and her role as business analyst was not satisfying. In fact, it was impacting her overall well-being. But, with a mortgage, three kids, and a husband who traveled three days a week, she questioned whether teaching was worth pursuing. She spent a lot of time thinking about it, planning for it, and researching the possibility, but daunted by the thought, she prevented herself from taking action. Ultimately, Jan decided not to suppress her desire, so she reached out to a local university and learned exactly what it would take to become a teacher. What Jan didn’t know until she fully planned and prepared to go after her goal is that because she was interested in teaching mathematics there were alternative paths to becoming certified. This first step of just determining the requirements gave her a clearer picture of the cost, the time commitment, and the different possibilities involved. Suddenly, Jan’s desire to teach was actually feasible because of the clarity she gained from that simply phone call. Jan went from thinking and hoping about a new career to taking the first step toward accomplishing it.

Technical Tip: Define what the logical first step is, something simple, and then take it. It’s likely a phone call, setting up a website, filling out an application, or making an appointment. Don’t let another day go by.

F#2: Fear of Not Making a Massive Contribution–small steps lead to long treks.

“A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” ~ Laozi

One of the major issues with pursuing our goals is that we live in a hero’s culture. We hear about amazing accomplishments and compare them to our own realities and the goals we have. We need to be sure that we use the right yardstick to measure what we are looking to accomplish and detail the incremental steps along the way that reinforce that we are making progress. Too often, our goals are so lofty that when massive change or intense contribution is not an immediate outcome, we lose track of the fact that small steps are the mile markers that indicate that we are moving forward. Somehow, our brains tend to associate small wins with a lack of achievement when that’s not an accurate picture. We see that a friend has 800 followers on Twitter, and it prevents us from even setting up an account. What would 10 followers say about me and my lack of initiative? But that fear prevents the 10 followers and the steps it takes to get to 800 and then 8,000.

This fear that paralyzes us, because our goals seem too audacious while our contributions appear minimal, doesn’t recognize that when big goals are broken down they represent a series of small practical steps. Anyone with a massive accomplishment will tell you that it took guts and no guarantees; it takes the first step and every step thereafter to realize any big win. Art Markman, author of Smart Thinking, tells HBR readers that “the people who do manage to accomplish their long-term goals create regular space to make progress on them” (2016). The idea is to take the first step toward a goal and then each step thereafter. Massive contributions are almost always an accumulation of smaller ones.

Practical Example: Let’s consider Jan, again. In taking the first step to realize her goal in becoming a teacher, she launched her project by learning that she doesn’t need to go back to school before becoming a teacher. She can apply for an alternative route. Because she already has a degree in accounting and mathematics, she can use that to pursue a teaching certificate. Even though it took her a long time to get started, the new career path is quite the opposite in terms of the approach she needs to take versus what she originally deemed the excuse. She thought she would need to getting a teaching degree to be able to teach, but because of her math background, she actually needs a teaching job to be able to get the credential. Little did she know that math teachers are in seriously high demand, and after applying at a local technical high school, she gave notice to her analyst position, and started in the new teacher induction program in August. A series of small steps, once considered too daunting to take, became easier and easier for Jan as she took each one at a time. She learned to create space in day to manage the progress, and she recognized that each small step added up to achieving her big goal. In June she considered teaching to be an impossible feat, and now in August she’s on staff in her dream job.

Technical Tip: New projects, initiatives, and goals can seem intimidating, but that’s because they have a number of moving parts. After identifying and taking the first step, unpack the rest by making a list of steps and action items that need to be taken. Prioritize them and get started on the process of completing them one-by-one, and make space daily and weekly for each. Incremental achievement is the only antidote to overcoming the fear that your accomplishments won’t be grand enough.

F#3: Fixating on the Wrong Measures–avoid thinking about the product, and focus on the process.

“In the long run, we shape our lives, and we shape ourselves. The process never ends until we die. And the choices we make are ultimately our own responsibility.” ~ Eleanor Roosevelt

Learn to measure success by celebrating the short-term wins rather than waiting for the long-range outcomes. Setting goals and having clear targets is a key to success because if you don’t know where you are going, you have no chance of getting there. However, we tend to overlook the daily inputs, tasks, and behaviors that need to be done throughout the journey that are necessary to be successful. Essentially, the day-to-day activities that will lead to accomplishment. Effective leaders focus not only on the long-term goals and the overall destination, but they also identify key mile-markers that indicate accomplishment and success along the way.

One by-product of identifying clear short-term measures while working toward a goal is in recognizing the clarity they bring during the process. Great leaders know how to anticipate potential problems and accurately measure risk, but they also know when the process is demonstrating new developments to celebrate incremental successes. Everything we do is riddled with complications and setbacks, but there are also always key indicators that we are making headway. The key is framing an understanding around each hurdle so that each minor accomplishment is a short-term win toward success, which is a critical element to not losing site that we’re realizing breakthroughs. In his fable about reaching goals, Ken Blanchard’s composite character Andy reminds readers that leaders have to cheer the work being done not just the product or outcome of the work (1997). Knowing that there are measures of success that come long before the goal is reached allows for failure to be an option along the way to our ultimate success, and it motivates us to keep on pushing forward.

Practical Example: Let’s take one last look at Jan. She gained clarity that her goal can actually be a reality and that she can fulfill her lifelong dream of becoming a teacher. Even though the requirements to becoming certified are easier than she thought, there are realities that she needs to be pragmatic about. Jan has a lot on her plate and since her husband travels a great deal, many of the household demands fall on her. Whether it is as simple as grocery shopping or taking the kids to their activities, they all require time and will add to the level of strain in doing a new job and going back to school at night. The key for Jan is that she stays realistic with all the incremental steps she previously identified. She has to recognize that there will be hurdles and setbacks, but she also needs to learn to celebrate the smallest of wins and remind herself of the overall goal whenever she experiences failure. One bad day at school doesn’t mean she’s not a good teacher just like one alternative routes course completed doesn’t mean she’s certified. She has to overcome the mistakes and celebrate the minor markers of success during the process of realizing her dreams.

Technical Tip: Become passionate about the process, not obsessed about outcomes. Learn to celebrate yourself and others along the journey. Too often we hear about people achieving so much and still being unsatisfied. When we set goals and look to achieve more, we are seeking something we hope pays off in some way. Whether it is self-satisfaction, a better lifestyle for your family, or making a positive contribution to your community, the key is to enjoy the process and gain knowledge and understanding from the experiences.

Avoiding the three Fs of failure is what defines and separates those who learn from life as a process, with repeated setbacks and failures, and those who don’t even take the first step to reaching their dreams. Our goal at TheSchoolHouse302 is to help you gain clarity around what you truly want to achieve and offer simple, yet effective, strategies for you to tackle the complexities of life. If you want more support with learning how to fail forward for yourself or the leaders in your organization, don’t hesitate to contact us, we can help.

Let us know what you think of this #SH302 post with a like, follow, or comment. Find us on Twitter, YouTube, iTunes, Facebook, & SoundCould. And if you want one simple model for leading better and growing faster per month, follow this blog by entering your email at the top right of the screen.

TheSchoolHouse302 is about getting to simple by maximizing effective research-based strategies that empower individuals to lead better and grow faster.

Joe & T.J.

References

Ashkenas, R. (2011). The problem with perfection. Harvard Business Review.

Blanchard, K. (1997). Gung ho! Turn on the people in any organization. New York: Ode to Joy Limited.

DeMers, J. (2015, July 07). Inspirational Lessons From the Failures of 4 Great Leaders. Retrieved from https://www.inc.com/jayson-demers/inspirational-lessons-from-the-failures-of-4-great-leaders.html

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. New York: Scribner.

Markman, A. (2016). When you should worry about failure, and when you shouldn’t. Harvard Business Review.

Thiel, P. (2014). Zero to one: Notes on startups, or how to build the future. New York: Random House, LLC.

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.

7 Mindshifts for School Leaders: Finding New Ways to Think About Old Problems.