Groundhog Day for School Leaders

I was in the Virgin Islands once. I met a girl. We ate lobster, drank Piña Coladas. At sunset, we made love like sea otters. That was a pretty good day. Why couldn’t I get that day over and over and over? ~ Phil Connors in Groundhog Day

February is home to a few special events, such as Valentine’s Day, President’s Day, the Super Bowl, and what we really look forward to at TheSchoolHouse302, Groundhog Day. Not only is this an important day that lets us know how many more weeks of winter we should expect, but it reminds us of the insightful and introspective comedy film, Groundhog Day, featuring Bill Murray as a cynical T.V. weatherman named Phil Connors.

Phil is begrudgingly on assignment covering the annual event in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. And, maybe because of his ironic behavior about the whole thing, Phil ends up stuck in time, living the same day, Groundhog Day, over and over again. He lives the same events, interacts with the same people, and consistently makes the same mistakes. The genius behind this film, and the point it raises for us as people and as leaders, is to question the approach we take each day in life and work. Phil learns as the days unfold in precisely the same way, that every time he awakes to the same song, we should see opportunities in life, not obstacles.

Once Phil realizes he’s stuck in a time loop, he first sees his situation as a curse. It isn’t until he learns how to live well with a full heart and good intentions that he brings his very best self to every situation, improving the lives of others, which eventually allows him to break free from the continual loop in which he is stuck. In the beginning, Phil is cynical, derisive, ungrateful, and curt. As he learns, in the end, he finds himself whole, he reflects, and he improves his ability to see the power in each day. He gains insight, and he also falls in love.

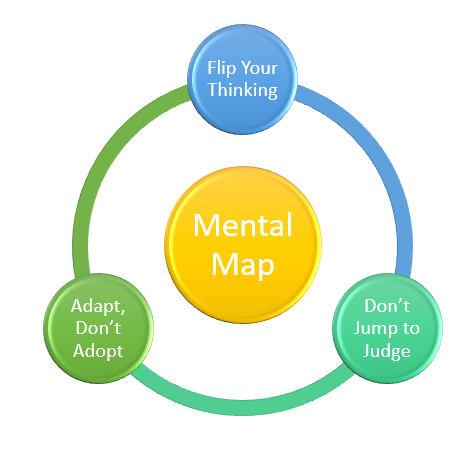

We don’t have the ability to redo days or to make them perfect. But, what we do have is the ability to manage our mental map–how we view ourselves and our world. We do have the distinct freedom in life to turn obstacles into opportunities. The following model provides three clear behaviors that will help school leaders to avoid the mental map trap of deficit and liability thinking.

A Mental Map for School Leaders

Minding Your Mental Map

As leaders, we have to be mindful of the map that our brains make of ourselves, other people, and the world around us. The average person has between 12,000 and 60,000 thoughts per day with up to 95% of them repeating themselves. In other words, 95% of the thoughts we hold at any given moment are occupying space that they have already occupied in the past 24 hours. And, considering that 80% of our thoughts are negative, that’s a lot of unproductive time and energy. Negative thoughts are a liability for leaders. We call this “liability thinking” because the thoughts are burdensome, blur our thinking, and limit our ability to move ahead, forcing us into a recurring scenario. Negative and limiting thoughts are like Groundhog Day because when we live in their shadows, the future we predict is blurred by bad weather. We can get stuck in the same place, repeating our lives, through our thoughts and actions, in an unproductive way. But, that doesn’t have to be the case. We can learn to look at opportunities instead of obstacles. We can learn from what happened to Phil Connors.

#1. Flip Your Thinking

We have to remain sensitive to our own thoughts to make sure that they are not sabotaging our personal and professional success. How we think and see situations has consequences regarding our ability to successfully navigate through complex situations. The answer often runs counter to our innate ability to generate solutions to common problems. It means that we have to flip our thinking, taking the following approach to thoughts and ideas:

Focus on what you want, not what you don’t want.

This seems odd at first, but the language we use, out loud and in our minds, is powerful. As Judith Glaser says, “our words create worlds.” Next time you find yourself saying something like, “I don’t want to be overweight, I need to lose ten pounds.” Flip it and say, “I want to be fit and I’m going to lose ten pounds.” Loss aversion, according to psychologists, creates a strong response in our brains to avoid setbacks versus looking toward progress. It’s the negative “expression of fear” versus the positive outlook. Flip your thinking by flipping the language that you use.

Foresee opportunities, not challenges.

Our primal nature is designed to recognize potential threats and challenges. In many respects this is important, safety being the first, But, it also means that we can become mired in the obstacles in front of us instead of the possibilities that await us if we flip our thinking. In his book How Successful People Think, John Maxwell reminds us that our thinking is what makes for great leadership. How we think, what we think, when we think, where we think, and with whom we think are all important. Successful school leaders learn to explore “possibility thinking,” which changes the path of our energy toward “accomplishing tasks that seem impossible.” Possibility thinkers believe in solutions. One technical way in which this can be done is through the use of a SWOT analysis, focusing intently on opportunities, not threats, as we work to make big things happen.

Think with your team.

Too often, especially when challenges arise, school leaders turn inward and work to solve problems in isolation. Instead of saying more and explaining their thinking, they keep it to themselves. Flip your thinking from an internal monologue to an external dialogue. Use your team. Every thought that a school leader has doesn’t need to be a fully realized great idea. In fact, the best ideas come from gathering perspectives. Great teams don’t just work well together, they think well together too.

#2. Don’t Jump to Judge

The best leaders know the appropriate times to play the role of the judge, and those times are rare. But, as evaluators, supervisors, observers, and performance appraisers, we often find it hard to take off the boss hat so that we can truly come alongside others versus looking down from above. The key is knowing the difference between coaching and judging, being able to see positive intent, and working to empower people to have a voice on the team.

There’s a difference between a coach and a judge.

One key to making sure that you don’t become a judge when you’re looking to coach is to remain conscious of what it means to build buy-in from your boss, your team, and your employees. When we judge a person or situation, especially without constructive criticism, we break down the connection that we need to be able to coach. In Conscious Coaching, Brett Bartholomew reminds us that coaching is best when it’s with someone, not to them. We must remember to be in the moment, experiencing it with the people, rather than passing judgment after the fact. The best coaches stop the game and call the plays; they don’t just scream in the locker room.

Always assume positive intent.

Assuming positive intent, especially when someone does something that seemingly goes against the core values of the organization or directs judgment in an unhealthy way, is really hard to do. Great school leaders can have really good “intent antenna” but not all antennas work perfectly every time. For that reason, we have to take a step back from these difficult circumstances to analyze intent before coming to any conclusion. Insteading of jumping to judge, “the first crucial step is to let any initial upset subside. Emotional business decisions–especially those based on anger or fear–are rarely good ones.” Stepping back gives us time to evaluate, which is important because we typically judge ourselves by our intent and others by their actions. Let’s flip that and become more critical of our own actions while exploring the intent behind what others do.

Empower people to be open to giving and getting feedback.

According to Stone and Heen, giving and getting feedback is incredibly difficult for three reasons: it can simply be inaccurate, it might be coming from someone we don’t respect, and we take it to heart that it’s about ourselves versus our work. The problem with anything that thwarts or stalls a cycle of feedback is that it doesn’t support our growth the way that feedback can when it’s healthy and received well. For feedback to be a norm, leaders have to model an identity that growth is important for everyone. We communicate the need to get better, we empower people to give us feedback, and others will accept our feedback in return. The key is in developing a culture where everyone has a desire to learn, grow, and improve in our efforts to reach toward excellence through candor and compassion. It all starts with giving and getting feedback.

#3. Adapt, Don’t Adopt

Some school leaders fall into the trap of thinking that adopting a canned program or embracing a certain ideology will be enough. There is no doubt that there are models of excellence that can be effective, but for the long-term health of the organization, school leaders must ensure that any program they bring on is aligned with the core values of the school or district. When leaders simply adopt a program it rarely works, mainly because the staff will lack ownership and many will hang on to the old adage that “this too shall pass.” We always hope that these new programs will overshadow our problems and meet our needs. But, the problem is that many of the programs are mere band-aids to the real problems that need to be addressed, some of which are persistent in ways that programs can’t handle. The better response is to adapt your initiative to fit the school, not the other way around.

Suffering from perceptual illusion.

Too many school leaders suffer from the inability to accurately see a situation in its true light. One of the reasons is due to “perceptual illusion,” which is when we hold a perception as true due to the way it appears in our minds yet this “truth” is actually a misperception of the actual nature of a person, place, or thing. We contend that this is primarily due to a lack of solid foundational knowledge or a gross generalization of something that we think we understand but don’t. People who suffer from perceptual illusions aren’t the same as people who are simply “full of it.” Perceptual illusions actually create the reality that we know something when we don’t. Whether it’s a lack of practice, experience, research, or arrogance, the illusion prevents growth, gains, relationships, etc. from progressing the way we believe they should. The only way to avoid this cognitive deception is to work hard to really learn in new areas of our lives. Read the books you buy, seek out experts, and remain intellectually humble. Don’t simply adopt an idea until you know it well enough to adapt it.

Use multiple sources to connect the dots.

There’s always more than one authority on a subject. Great leaders know how to curate tons of information, synthesize new ideas, and communicate them for a change in practice. The problem is that we can get caught up in thinking that one source or one guru has the answer to a given problem. To build a unique culture, school leaders need to take into consideration as much expert advice as possible and then make something altogether new. Influential leaders possess divergent thinking, which “is the ability to uniquely connect new information, ideas, and concepts that usually fall far apart. People with this skill can match dissimilar concepts in novel and meaningful ways and uncover new opportunities that others may overlook.” Fidelity to a program, process or even diet is one thing, but adopting a practice from one source of information is destined to fail within a culture that has its own set of beliefs and behaviors. As Seth Godin always says, “without a doubt, the ability to connect dots is rare, prized, and valuable. Connecting dots, solving a problem that hasn’t been solved before, and seeing the pattern before it is made obvious, is more essential than ever before. Why then, do we spend so much time collecting dots instead?” Stop collecting single dots and start seeing their connections to move ahead.

Mold to fit and flourish, don’t crush and crash.

Great school leaders build; they don’t bust. Yes, great leaders know how to disrupt, but they do it productively by moving the team forward. Too often disruption and transformation are confused and replaced by an out-with-the-old, in-with-the-new approach. Even the worst practices can be blown up with enough pieces to put back together versus bashing everything to oblivion and starting fresh. One benefit to employing people who have the “impulse to break” things is that their “flashy ideas may energize and inspire others,” but those who value building something tend to stick with projects, teams, and organizations much longer, playing the long-range game to flourish beyond any seemingly quick fixes. It’s far better to mold what you have than to end up with nothing at all.

Conclusion

Persistent people have the ability to change the trajectory of their lives as well as the lives of others. They push past the mundane, seeing a future that is bright and different from the present. “Resilient people actually resist illnesses, cope with adversity, and recover quicker because they are able to maintain a positive attitude and manage their stress effectively.” The key to leading yourself and others is being able to see the silver lining while the gloom is taking place, not after. To do so, we often have to flip our thinking, empower others, and adapt something new to meet our needs. It took him a good while, but when Phil Connors made the switch in Groundhog Day, he ended up happier than before he got trapped in the loop. When we mind our mental maps, we can get ahead by seeing beyond the shadows of where we stand.

As always, we want to hear from you. Please hit us with a like, a follow, a comment, or a share. It helps us and it helps other readers, like you, to find our work so that more school leaders can lead better and grow faster.

We can’t wait to hear from you.

0 Comments